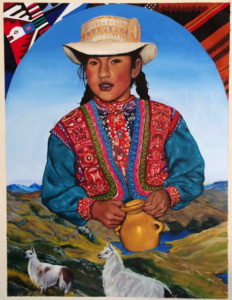

Layqa Nuna Yawar paints with intention. His compositions require quiet meditation and reflection as they are often larger than life and filled with the stars, ancestors, and community histories. His work is usually ephemeral, subject to weather conditions and whitewashing, but he enjoys working in public spaces. In an article from 2013, he said, “it’s about the interaction with people, going outside and interacting with kids and families to show them a different perspective. If we change the perspective we can change a person, if we change a person we can change a society.”

He still believes in society, even in the current political climate. He jokes, “I’ve never been able to look democracy in the face and not laugh.” In his youth he watched several presidencies dismantled by populist movements and military coups as the title changed from Abdalá Bucaram to Fabián Alarcón to Rosalía Arteaga and back to Fabián Alarcón before ending with Jamil Mahuad, all within one year’s time.

“Migration is what you did if you wanted to get ahead,” he tells me as he explains how his family, who came from the mountains, moved around Ecuador looking for new opportunities before they began to migrate to New York and New Jersey when he was just a child and even before. Layqa explains, “in the late 80s and early 90s, Ecuador went through political disarray and total chaos for a long time. It became economically unstable. And at the same time, El Niño came through and destroyed the coast.”

As his family looked for refuge, relocating one by one, Layqa stayed in Ecuador, straddling two cultures and nurturing the drawing skills acquired from an older brother, who treats art as a hobby and makes a living as an Electrician. They both inherited their passion from their mother–who as a girl, would make maps. But while she was never in an environment to practice her craft, Layqa explains, “I get to have an education in art and can pursue this as an option.” As he finishes an email confirming an upcoming project, he continues, “but with that privilege comes a lot of responsibility.”

I am writing curriculums invested in the idea of creatively reflecting voices.

He once said, “I see myself as a medium to the stories that are not told or the people that are not being seen,” and his work produced as a teaching artist for organizations including Young New Yorkers and City Without Walls have proven this to be true. “All of the participants have talent and they know their community. The only difference between us is that I have experience.”

However, his path to art was not set in stone. For a while, he was invested in becoming a doctor or a lawyer to fulfill the prophecy of “the American Dream” that his parents set in motion when they settled in the States. He eventually decided on psychology before a painting class derailed his plans. Since he has channeled any guilt into developing a pedagogy and uses his unique talent for presenting stories visually. He has become an expert at knowing what to listen for.

Migration remains a cornerstone of his work, “I think I am traumatized by the migration…my whole life has been influenced by it,” the artist tells me. He was only 14 when he made the move, but distinctly remembers selling his prized possessions, including his Nintendo and arriving in New York–allowing himself a month to become acquainted with his new home. “That curiosity is something I get to relive every time I travel.” The self-proclaimed ‘agitator’ lives for the discomfort of the unknown. He has traveled the world working throughout El Salvador, Paraguay, and the United States, “I like to be in places where I don’t know what the fuck I am doing, so I am always trying to build that pressure.”

The artist lives and works in one space a short walk from the Newark Penn Station. In fact, his bed overlooks his studio corner where research materials are taped up for inspiration and modern-day hieroglyphics–the everyday vernacular of cities–speckle the walls. In the way that Christian Iconography communicated with imagery over words to tells stories, he seeks to communicate oral histories with symbols, including those of migration. He has reworked the iconic Immigrant Crossing family* over the years, but would never claim it as his own. He considers powerful images–ones that become engrained in the public memory–to be public domain.

The artist lives and works in one space a short walk from the Newark Penn Station. In fact, his bed overlooks his studio corner where research materials are taped up for inspiration and modern-day hieroglyphics–the everyday vernacular of cities–speckle the walls. In the way that Christian Iconography communicated with imagery over words to tells stories, he seeks to communicate oral histories with symbols, including those of migration. He has reworked the iconic Immigrant Crossing family* over the years, but would never claim it as his own. He considers powerful images–ones that become engrained in the public memory–to be public domain.

*The Navajo graphic artist John Hood created the silhouettes in 1990 to make peace with the fleeing families he witnessed during his tour with the Marine Corps. The image has been adapted for yellow caution signs that until recently, dotted the highways along the US/ Mexico border. The imagery became so ubiquitous that it was even adopted by groups including the Minutemen for anti-immigration agendas.

We all have the right to go where we want. We are humans.

Since we met last April, the artist filmed a short, Motherland, with the filmmaker, Jess X Snow, studied with the master printmaker Randy Hemminghaus as part of the Brodsky Center Residency, and completed murals around the world. Visit the artist’s website and add him on Instagram to keep in touch.

organize | agitate | resist

LNY spoke with Diana Ledesma at his studio in Newark on April 17, 2017.

Images courtesy of the artist.

About the author:

Diana Ledesma is an arts professional living in New York City. She obtained her masters from New York University in 2016, completing her thesis on the status of the Mexican American art market.