G abriel García Román moved to New York 17 years ago to change his life and although the move from Chicago, where he basically grew up, played out differently than expected, he found confidence and his artistic voice in the city and it has become his home. He resides in Harlem, near 125th Street, in an apartment that provides a back yard studio equipped with a Dewitt table saw for frame making, and ample space for his varied endeavors including Chine-Collé, clothing design, jewelry making, and embroidery. However, as suitable as his apartment is for his craft, the biggest selling point is it is only an 18-minute bus ride from the print studio at his alma mater, where he continues to volunteer in exchange for studio time.

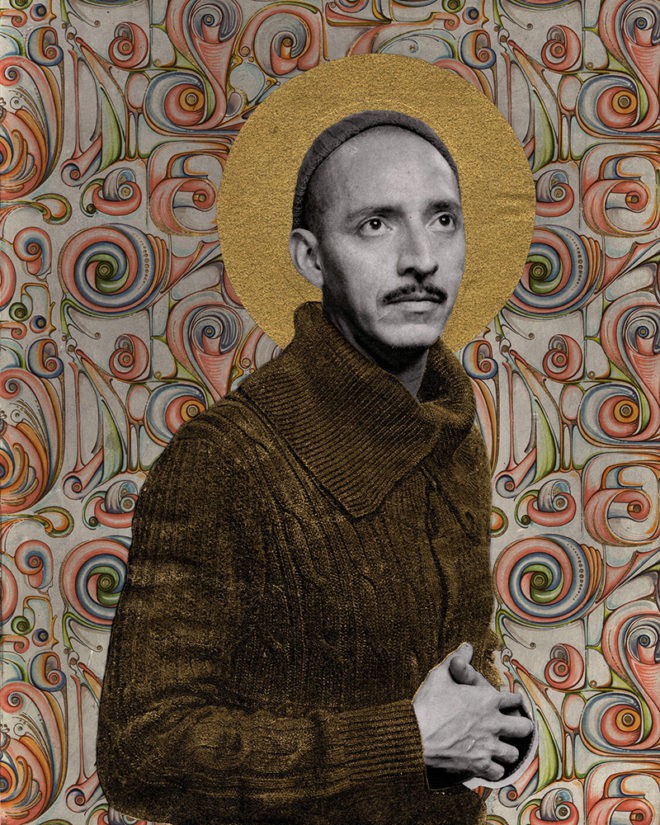

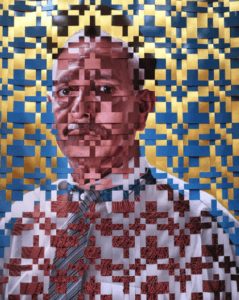

Román has always been interested in art making but never drew. To this day he doesn’t sketch his designs. His finished works are a reflection of his inner vision and artistic ability. The artist graduated from City College of New York in the 2010s with a bachelor’s in studio art and a love for the intaglio process known as photogravure. The college provides access to a large exposure unit that etches his digital image onto a plate with a light-sensitive film. He uses black ink to cover the etching completely, wiping away the excess with an old rag and the palm of his hand. At this point, Román could transfer the image onto a clean sheet of white paper, but for the series he has been working on since 2011, known as #QueerIcons, his subjects, or Santos, are further adorned with elaborate papers using archival glue, in a process known as Chine-Collé.

R

omán has always considered himself shy. He shared that he would be surprised if any of his classmates recognized him at a high-school reunion, because he mostly kept to himself.

I became an expert at being invisible because I was in the closet. I didn’t want anyone to know my little secret, so the less you heard from me, saw me, and remembered me, the better for my secret.

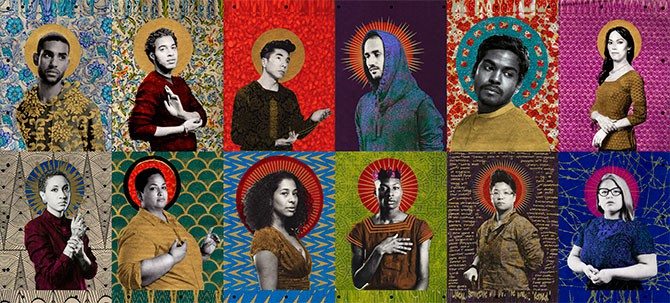

Fortunately, for the rest of us, Román escaped the confines of his ‘closet’ and found a way to protest the white-washing of art history. He explained that while studying art in college, the lack of positive brown or queer imagery was painfully obvious. “That was that impetus to this project,” which is now in its 5th year with more than 45 portraits completed. In the project’s current incarnation, Román has personalized the portraits further by adding the sitter’s hand-written message with a golden screenprinted layer.

The artist captures his subjects using a digital camera in a make-shift studio in his living room. He asks them to wear clothing that reflects light such as denim, wool, leather, or nylon and to avoid whites and text. However, adornments of the jewel or ink persuasion are encouraged. While we spoke, Román was working on four new prints of an icon, Yosimar Reyes, whom he met at the opening for his Queer Icons mural featured at Galería de la Raza in June 2016.

Román prefers when the sitters allude their confidence, often directing them to focus their gaze on his lens, to confront the audience directly with their power. He tries to include their hands “because there is something tender and telling about a person’s hands.” After all, his hands are his tools.

I

n 2016, the artist had his first solo show in New Jersey at Gallery Aferro in Newark. The exhibition was called, To My Father, and coincidentally opened on his father’s birthday. Román had a strained relationship with his dad. He left home when he was only a teen and created a very different life for himself. Recently, after his father’s death, he realized that their relationship was very different than the one his father had with family friends or neighbors and he began to appreciate Eulogio García in a new way.

When I was a kid I would cringe when somebody would tell me I looked like him. I hated his drinking, his smoking and how stern he was with us.

For this exhibition, however, Román embraced the resemblance and wove their images together.  “Now that he’s gone I have learned to respect his struggles and appreciate all of the knowledge he has bestowed on me.” His father always worked with his hands in factories or at home. Growing up, Román was his assistant, fixing pipes or painting walls, whatever was necessary.

“Now that he’s gone I have learned to respect his struggles and appreciate all of the knowledge he has bestowed on me.” His father always worked with his hands in factories or at home. Growing up, Román was his assistant, fixing pipes or painting walls, whatever was necessary.

For the better part of a decade, however, he kept his distance from his dad and made his own family of American artisans. When he mentions ‘family’ he is most likely referring to the Colombian and Puerto-Rican families of his best friends that he has been spending his Christmases with for several years now.

When he was 33 years old his parents retired to Zacatecas and Román began a regular pilgrimage to his birthplace to get to know them as human beings as well as understand his place in the world. As much as he is proud of where he comes from, it took visiting Zacatecas to learn that he is no longer a ‘Mexican.’ He has a vivid memory of the customs woman in Mexico City telling him that she did not believe he was a native, despite what he or his passport claimed. After spending some time there, he realized that he doesn’t quite fit the mold of a 30-something Zacatecano. One would be hard-pressed to find anyone else unmarried and sporting skinny jeans and tennis shoes and that is okay. For now, he is happy being a Mexican-Amaricón artist.

Gabriel García Román met with Diana Ledesma on Wedensday, December 7th, 2016 in the CUNY Print Studio. Look out for Román’s upcoming exhibitions and residencies in 2017!

Further Reading:

About the author:

Diana Ledesma is an arts professional living in New York City. She obtained her masters from New York University in 2016, completing her thesis on the status of the Mexican American art market.